Zanzibar: A Tapestry of Beauty, Spice, and Resilience

Returning to Zanzibar in 2025, nearly two decades after my last visit in December 2007, felt like stepping into a vivid dream. That trip, the final stop of a month-long safari through Kenya and Tanzania by truck, ended with a vibrant New Year’s Eve at Freddie Mercury Bar in Stone Town, where music, laughter, and clinking glasses welcomed 2008. Now, the island’s turquoise waters and spice-scented air remain enchanting, but the rise of all-inclusive resorts and higher prices casts a bittersweet shadow. Beneath the paradise lies stark poverty, yet the resilient spirit of its people—especially the unexpected Maasai on its beaches—shines through.

Zanzibar’s food is a love letter to its history, blending African and Asian flavors. Curries laced with clove, cardamom, and cinnamon, alongside grilled seafood, burst with the island’s soul. Tanzania’s 30-plus spices—pepper, ginger, vanilla, and Zanzibar’s famed cloves—fill Stone Town’s markets, their aromas mingling with spiced teas. Sipping chai one afternoon, I felt the island’s heartbeat, a fusion of cultures in every sip.

This trip was a gentle escape. I swam in crystalline waters, snorkeled vibrant reefs, and watched dolphins leap against the horizon. A day on a white sandbank near Mnemba Island felt like a dream, though the equatorial sun demanded respect. I relied on coconut oil and a long-sleeve shirt, my hat a constant shield, to avoid burns. Since 2007, when Zanzibar felt like a hidden gem with uncrowded beaches, the island has changed. Resorts now dot the coast, and tourism’s footprint feels heavier. I hope locals, not just the government, benefit more from this boom.

The surprise was seeing Maasai men, striking in red shukas, selling crafts on the beach. Many come from mainland Tanzania, a link to my Serengeti visits where I learned of their beekeeping. Maasai honey, crafted by resilient African honeybees foraging on acacia and wildflowers, is raw, earthy, and floral—unprocessed and pure. Once a staple, it’s now a lifeline through projects like Maasai Honey and The Maa Trust, empowering women with income as droughts threaten pastoralist life. Beekeepers protect the land for thriving hives, fostering conservation. I didn’t buy honey this time, but its story lingered—a symbol of adaptation

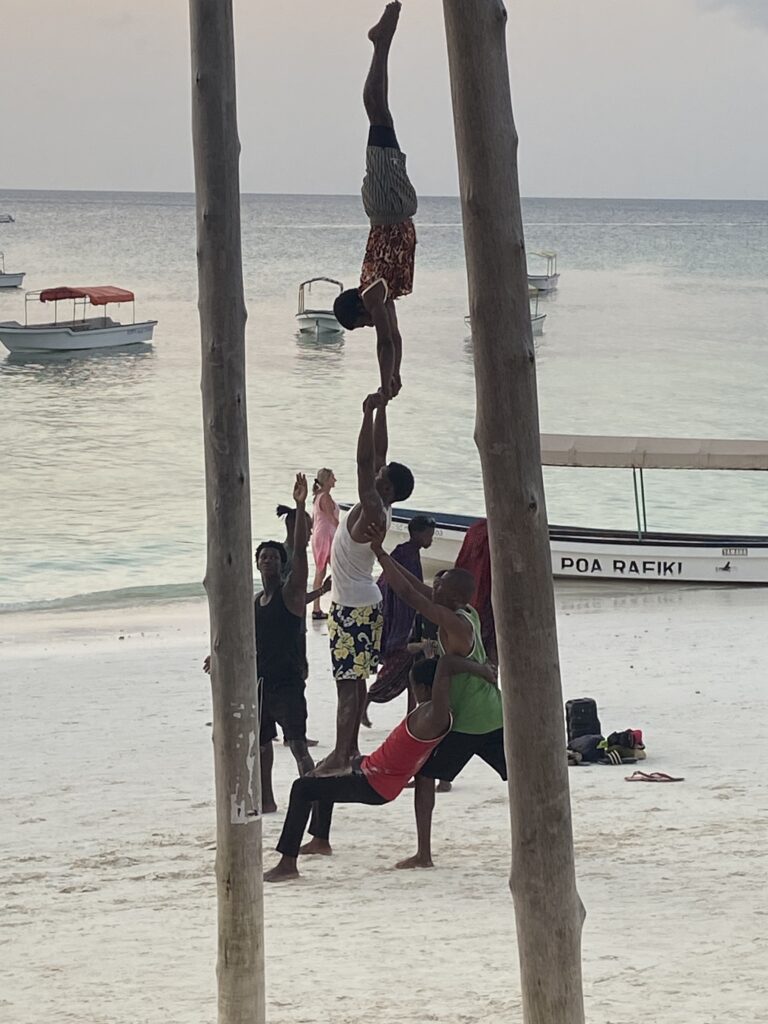

Poverty remains stark, visible in weathered homes and barefoot children, contrasting glossy resorts. Chatting with Lemayian, a Maasai from Arusha, I felt the island’s complexity—beauty and struggle intertwined. My ten days passed in swims, spice-laden meals, and fiery sunsets. By the end, I was ready for new horizons. As my plane lifted off, Zanzibar’s shores fading below, I carried memories of that 2007 New Year’s Eve and the island’s enduring essence—its flavors, its people, its contradictions. Here’s to the next adventure, and to Zanzibar, a place that lingers long after you’ve left.

Zanzibar’s magic lingers—spices, sun, and Maasai resilience weave a tapestry of beauty and struggle, from a vibrant 2007 New Year’s Eve to today’s crowded shores.